accesses since May 13, 2003

accesses since May 13, 2003 copyright notice

copyright notice

link to published version: Communications of the ACM, August, 2003

link to published version: Communications of the ACM, August, 2003

accesses since May 13, 2003

accesses since May 13, 2003

In a recent column in CACM (February, 2001), Peter Denning identified the four hallmarks of a "profession."

Denning added that professions include institutions for preserving the knowledge and practice, enforcing the standards, and educating professionals.

Although Denning's discussion related to Information Technology as a whole, I want to drill down a bit into a sub-discipline that deserves more recognition and separate status than it's currently receiving: networking or Internet forensics (hereafter just Internet Forensics). At this point, Internet forensics has not been fully appreciated because of it's proximity, historically and conceptually, with computer forensics - which I would argue is actually more different than similar from its networking cousin. As a result, the two tend to be evolving together, when they should be evolving separately.

MEETING THE FOUR CRITERIA

Denning argued that IT clearly satisfies the first two conditions, partially satisfies the last two, and is likely to satisfy all four within the next decade. He was also careful to distinguish disciplines and professions from crafts and trades, and to distinguish his broader interpretation of a professions from the narrower definition of a professions as a "set of people who have at least two years of post baccalaureate education and whose field is on an approved list" proffered by the U.S. Department of Education.

While not a profession, computer forensics satisfies the definition of a discipline. It is a well-defined field of study and practice. Like IT itself, it satisfies both the durability condition and the body of principles. It also has a codified body of practices that have evolved over the years through courtroom experience, and standards for competence, ethics and practice. The SANS institute (www.sans.org), for example, offers courses in computer security, and the Global Information Assurance Certification (www.giac.org) offers a certificate in Certified Forensic Analysis that requires renewal every four years and has a Code of Ethics (www.giac.org/COE.php) with which each certificate holder must agree. Standard textbooks exist, as do articles. It has conferences such as the Digital Forensics Research Workshop (www.dfrws.org) and peer-reviewed journals like the International Journal of Digital Evidence (www.ijde.org), just as one might expect of a rapidly maturing discipline.

Much the same may be said of network or Internet Forensics, but it occupies a far less independent role in the Computing Security community. In one of life's ironies, it was Internet security concerns that actually helped drive Computer Forensics to the disciplinary status it now enjoys.

COMPUTING vs INTERNET FORENSICS

There is no question that computer forensics is more familiar to the IT community. Today's Google search reveals 60,600 hits for "computer forensics," 3,250 for "network forensics," and 146 for "Internet Forensics." However, if one looks to the skilled practitioner community, one gets a very different view. As one datapoint, consider the following list of SANS course offerings (from the SANS training matrix on www.sans.org):

Track 1: SANS Security Essentials

and the CISSP CBK.

Track 2: Firewalls, Perimeter Protection and VPNs .

Track 3: Intrusion Detection In-Depth .

Track 4: Hacker Techniques, Exploits and Incident Handling .

Track 5: Securing Windows .

Track 6: Securing Unix .

Track 7: Auditing Networks, Perimeters and Systems .

Track 8: System Forensics, Investigations, and Response .

Track 9: SANS Information Security Officer Training .

Track 10: IT Security Audit Essentials .

Track 12: SANS Security Leadership Essentials for Managers .

If we eliminate the basic, vanilla tracks (1 and 12), we see that of the remaining ten tracks, only one (Track 8) focuses on computing forensics - 90% are oriented primarily toward topics within network security, the detection and analysis aspect of which is Internet Forensics. So how is it that Internet Forensics is so little known outside the community that practices it?

The answer lies in the source of the inspiration of these two areas. Computer Forensics was championed early on by law enforcement, and fits well within its overall investigative methodology. Internet Forensics, on the other hand, evolved as a response to the hacker community. In fact, Internet Forensics specialists have essentially the same skill sets as their adversaries. This is not the case in Computer Forensics.

THE ORIGIN OF "FORENSICS"

The art of forensics derived from the practice of forensic medicine, which was already recognized as a medical specialty by the end of the eighteenth century. The most common forensic activity in this area is the autopsy or postmortem examination, based on a general knowledge of the anatomy inherited from Pharaonic Egypt and ancient Greece although the association between the state of the anatomy and the cause of death remained the subject of wild speculation until well into the last few hundred years.

As forensic medicine evolved from the study of anatomy, criminal forensics evolved from the study of fingerprints. So far as I can determine, no proof exists that it is impossible for more than one person to have the same fingerprints. According to Gordon Dechman, President of Fingerprint USA (www.fpusa.com), "Fingerprint patterns are genetically established but the actual ridge structure is developed through a chaotic process, and the probability of identical fingerprints is very, very small. Fingerprints are accepted by all courts world wide as positive proof of identity, and a considerable body of knowledge has been established and is legally accepted regarding fingerprint identification methods." The British standard, for example, holds that if two fingerprints share sixteen characteristics, they are from the same individual. Fingerprints have been routinely taken, categorized, and filed for over 100 years, and since the 1980s have been digitized, stored, shared and compared on networked computer systems. This evolutionary path to computation came at a time when computers moved beyond calculation to media processing, so law enforcement investigators and prosecutors were driven to increase level of technology in their skill sets.

So the concept of "forensics" is anything but new. However, its use in the IT arena began in the last few decades as "computer forensics."

COMPUTER FORENSICS

As mentioned above, the widespread use of computer forensics resulted from the convergence of two factors: the increasing dependence of law enforcement on computing (as in the area of fingerprints) and the ubiquity of computers that followed from the microcomputer revolution. As computer forensics evolved, it was modeled after the basic investigative methodologies of law enforcement and the security industry that championed its use.

Not surprisingly, computer forensics is about the "preservation, identification, extraction, documentation and interpretation of computer data" (see Kruse and Heiser reference below, pp. 2). In order to accomplish these goals, there are well-defined procedures, also derived from law enforcement, for acquiring and analyzing the evidence without damaging it and authenticating the evidence and providing a chain-of-custody that will hold up in court.

The tools for the "search-and-seizure" side of computer forensics are a potpourri of sophisticated tools that are primarily focused on the physical side of computing: i.e., tracing and locating computer hardware, recovering hidden data from storage media, identifying and recovering hidden data (e.g., watermarks - see this column in November, 1997 CACM), decrypting files, decompressing data, cracking passwords (see Figure 1), "crowbarring" an operating system (bypassing normal security controls and permissions), and so forth. For those who are old enough to remember the original Norton Utilities for DOS, think of these modern tools as the original Norton Disk Editor for DOS on steroids.

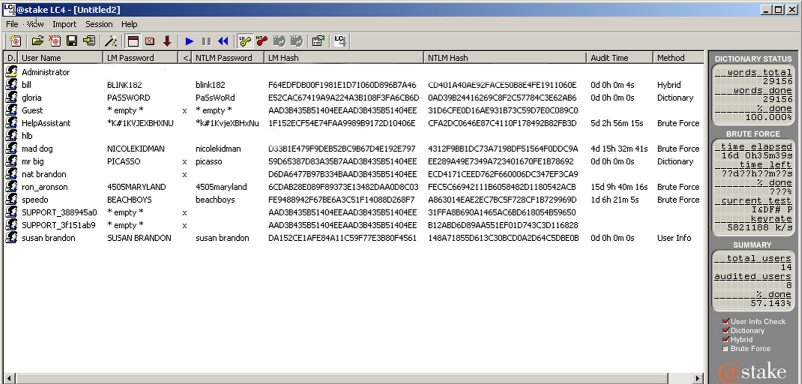

Figure 1: Password Cracking on Windows XP with the latest commercial version

of L0phtcrack, LC4 (atstake.com).

Some noteworthy observations: (1) HelpAssistant, and "Support" accounts

and passwords ship with XP - there's no way to get rid of these accounts - hmmmm.

(2) LC4 does the "cracking" on the old Lan Manager (LM) hash technology

inherited from OS/2 which is relatively trivial to break. NTLM passwords involve

a relatively robust password hashing algorithm, but that advantage is removed

by default because XP automatically converts NTLM to the easily breakable LM

hash for backward compatibility. Given enough time, LC4 will break every LM

hash, so the "fix" is to disable the LM hash capability in the Registry

and sacrifice the backward compatibility. (3) We ran LC4 on this workstation

for a bit over 16 days (57% of a complete run), and recovered all but 3 passwords.

(4) Three of the passwords were cracked in under 1 second! (5) LC4 can be deployed

over a network!!

Listed below are some common categories and a few examples of computer forensics

toolkits:

Most computer forensics vendors offer a variety of tools, some even offer complete suites. But the links above will provide a useful, high-level overview of the world of computer forensics and the tools used therein.

A cursory review of this list suggests tools that are not mainstream for the typical computer villain.

INTERNET FORENSICS

Now the rubber meets the road. We observed that the impetus for computer forensics came from law enforcement - a community that arrests, investigates, seizes, stores and locks up physical objects. The computer forensics specialist's adversary, in all likelihood, is a computer-using criminal with no particular skill level beyond that of a typical end-user. Such is not the case with Internet Forensics

A cursory review of this list of computer forensics tools suggests that they are not in widespread use by the typical computer villain. The pornographer might use a graphics tool to morph the images into something unrecognizable immediately, but that's unlikely to be anywhere near as challenging as doing a reverse-morph on an unknown file format. The computer forensics specialist works on a different plane than the person he/she is investigating.

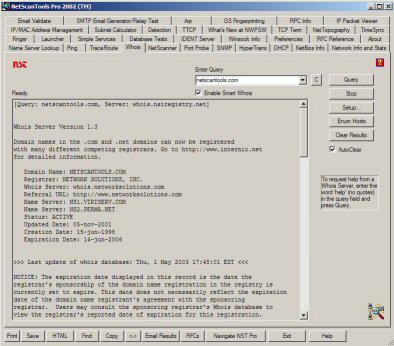

To the contrary, the Internet Forensics specialists uses many of the same tools and engages in the same set of practices as the person he/she is investigating. Let me illustrate with a few examples by reference to Figure 2.

Figure 2: One of the more full-featured network tools, NetScanTools Pro (www.netscantools.com).

Note the abundance of features built into one product!

Suppose that you've received some suspicious email, and want to verify the authenticity

of a URL included within. A number of options are available. One might use a

browser to access information from the American Registry for Internet Numbers

(www.arin.net). Or one might use any number

of OS utilities. But we'll save ourselves some time and worry, and use a general

network appliance, NetScanTools Pro (see Figure 2-). We see from the figure

that in this case we identified the registration, domain name servers, currency

information, etc. for netscantools.com.

Now let's change the scenario slightly. Suppose that we had some hostile intent, and wanted to ferret out information about some company's network infrastructure. What tool might we use. You guessed it, NetScanTools Pro. The point is that the self-same tool is equally useful to the hacker conducting basic network reconnaissance and the legitimate Internet security specialist who's trying to determine whether a URL links to a legitimate company or a packet "booby trap." The point is that, both uses require essentially the same skill sets.

Don't get me wrong, I am not suggesting that NetScanTools Pro is a hacker tool. It is a general-purpose network analyzer. I use it all the time to analyze my networks and to explain network analysis issues to my students. But in order to serve in that capacity, it must also have the capabilities to be misused by hackers. In Internet Forensics it is customarily the case that the forensics specialist undergoes the same level of education and training as the hacker he or she seeks to thwart. The difference is one of ethics, not skill. We observed that this was not true of the perpetrator and investigator in computer forensics.

To drive home the point, look at the other options that NetScanTools Pro provides. One can use an ICMP "ping" to identify whether a particular network host is online just as easily as one can use it to identify activity periods in network reconnaissance or a network topology. One can use a Traceroute to determine network bottlenecks, or to identify intervening routers and gateways for possible man-in-the-middle attacks. One can use Port Probe to verify that a firewall is appropriately configured, or to make a list of vulnerable services on a host that may be exploited.

Where computer forensics deals with physical things, Internet forensics deals with the ephemeral. The computer forensics specialist at least has something to seize and investigate. The Internet forensics specialist only has something to investigate if the packet filters, firewalls and intrusion detection systems were set up to anticipate the breach of security. But, if one could always anticipate the breach, one could always block it. Therein lies the art, and the mystery.

CONCLUSION

If I've been successful, I've got you thinking about the fundamental differences between computer forensics and internet forensics. I think that on careful analysis, one has to conclude (a) that these are fundamentally different skills, (b) that in the case of Internet forensics, the skill sets of the successful perpetrator and successful investigator are pretty much the same, and (c) Internet forensics is as much a discipline as it's search-and-seizure counterpart.

This validity of these conclusions may be confirmed in any number of ways. For the most part the tools-of-the-trade for both hacker and Internet forensics specialist are the same, though the occasional extreme case like Dug Song's Dsniff (monkey.org/~dugsong/dsniff/) challenges this generalization. It's hard for me to imagine a legitimate, lawful use of Dsniff's "macof" utility that enables the users to flood switch state tables! But in the main, the hacker and the Internet Forensics specialist could co-exist with the same tools and equipment.

There is also a parallel in the flow of the network traffic. Ingress traffic to the analyst is egress traffic to the hacker, v.v. The same packet crafting technique that verifies true stateful inspection of fragmented packets also launches exploits like Teardrop and Ping of Death. Indispensable tools for packet capture and analysis like tcpdump are, by definition, capable of promiscuous packet sniffing, as are intrusion detection systems like Snort. The underground hacker community and the Internet folks with the white hats are birds-of-a-feature if one ignores the direction of their moral compass.

This is the time to change our focus from the negative (hacker) to the positive (Internet Forensics Specialist) dimension of this exciting new discipline, and to begin to take the differences between computer forensics and internet forensics seriously. To make the distinction complete, we need to add a few publications in Internet Forensics as SANS has already achieved near perfection in the conference arena, and GIAC already has established certification standards that seem to be universally accepted. If we can break from the tradition of including Internet Forensics (under some name or other) as the penultimate chapter of a Computer Forensics textbook, and mislabeling the excellent word already done in the field under the theme of "reverse-hacking" we'll be well on our way to completely articulate Denning's durability, body of principles, body of practices and standards for competence, ethics and practice tests for a genuine profession.

For Further Reading:

A good introduction to computer forensics is Warren Kruse II and Jay Heiser's, Computer Forensics, Addison-Wesley, 2002.

There are quite a few good books on Internet Forensics, though the term is not widely used yet. Three of the best are:

Note that the theme of all of these books is "hacking," the opposite of which is Internet Forensics. To learn one, you learn the other.

The premiere password cracking tool is L0phtcrack, and it's commercial version LC4. Additional information may be found on the @stake website (atstake.com) or though a Web search on "l0phtcrack" (note: the second character is a zero).